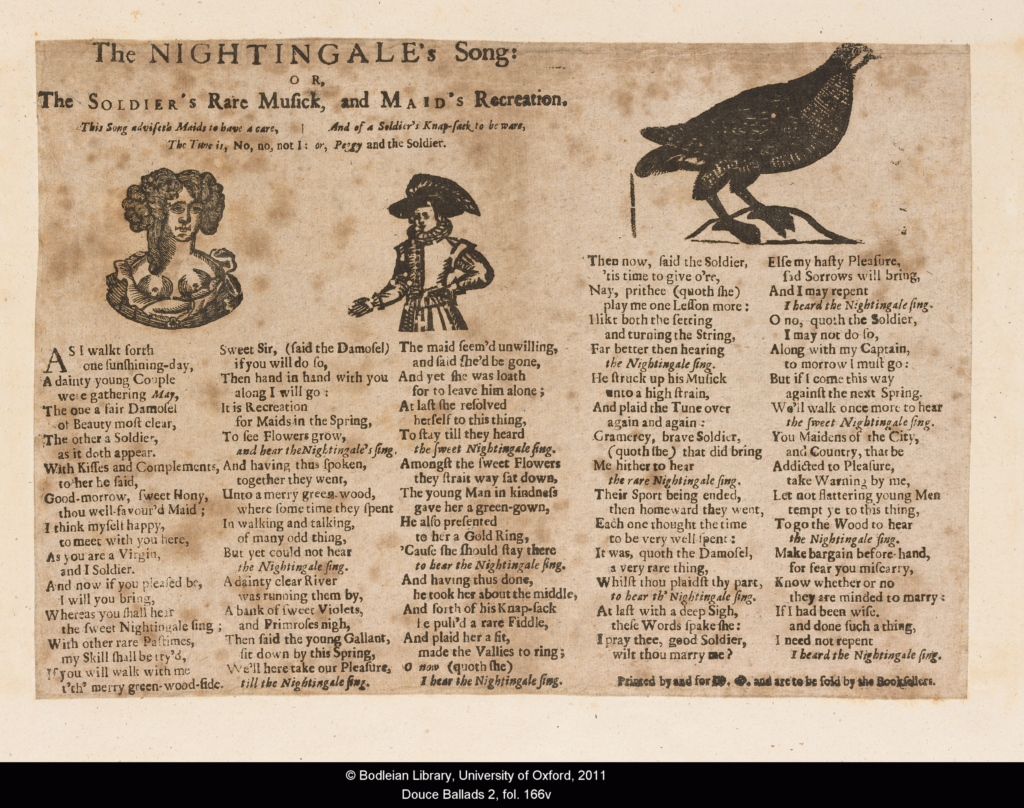

Also having been called “One Morning in May” and “The Bold Grenadier”, it seems to have first appeared as a broadside ballad in the very late 17th century under the title of “The nightingale’s song: or The Soldier’s Rare Musick, and Maid’s Recreation”, (published by W Onley of London), but with a possible earlier and similar song from 1639. The lyrics vary according to the singer or the publishing, but in short, the narrator recounts strolling along one day to come across a lovely young woman and her soldier lover and the interaction between them. The Roud Folk Song Index lists it as song #140, and although English in origins it did make its way over to the US where it became part of the Appalachian ballad tradition in which it is often called “The Soldier and the Lady”, or “The Irish Soldier and the English Lady”. It was brought to recent folk-song relevance by the singing of Liam Clancy/the Clancy Brothers, and by the Irish Rovers. A superbe page on a more complete history of this song can be found at Joop’s Musical Flowers.

Side commentary: This was the first song I worked on when I began to play concertina. It wasn’t long before I received criticism for “perpetuating outdated stereotypes” as it is clear that a married man is seducing a young woman. So, permit me to point out that all of these songs are reflections of the human condition and social commentary in of themselves. If you intend to get involved in folk music, it will clearly come with warts and issues you may have doubts on. But it is not music to reflect your own personal morals, and if you should take issue with a song, it is best that you not sing that song and find another one that pleases you. Scolding a singer for presenting a historical ballad makes you the problem; not the singer.

Jos. Morneault

. C G C

As I was a walking and a rambling one day[1],

. C D C D C G

I spied a young couple so fondly did stray.

. C D C G

And one was a young maid, so sweet and so fair,

. C D G C

And the other one was a soldier and a brave Grenadier.

CHORUS:

And they kissed so sweet and comforting as they clung to each other.

They went arm and arm down the road like sister and brother.

They went arm and arm down the road till they came to a stream,

and they both sat down together, luv, to hear the nightingale sing.

Well out of his knapsack he drew a fine fiddle.

And he played her such merry tunes that you ever did hear.

And he played her such merry tunes that the valleys did ring.

“Oh, softly,” cried the fair maid, “hear the nightingale sing.”

Chorus.

“Now I’m off to India for several long years[2],

“Drinking wine and strong whiskey instead of pale beer;

“But if ever I return again, it will be in the spring,

“And we’ll both sit down together, Luv, to hear the nightingale sing.”

Cho.

“Oh then,” said the fair maid, “will you marry me?”

“Oh no”, said the soldier, “however can that be?

“For I’ve me own wife at home in the old country,

“And, sure, she is the fairest little thing that you ever did see.”

Here is an American variant that I gleaned from John Renfro Davis at https://contemplator.com/america/nighting.html, who writes << It appears in Sharp & Karpeles Eighty Appalachian Folk Songs. There is a different song named The Nightingale which begins, “My love he was a rich farmer’s son.” These words are similar to several verses of a broadside in the Bodleian Library which was printed in 1675 by W. Olney of London. It is titled The nightingale’s song: or The soldier’s rare musick, and maid’s recreation and it is noted as being sung to the tune No, no, not I.>>

One morning, one morning, one morning in May

I spied a young couple all on the highway

And one was a lady so bright and so fair

And the other was a soldier, a brave volunteer

Good morning, good morning, good morning to thee,

Now where are you going my pretty lady?

I’m going to travel to the banks of the sea

To see the waters gliding, hear the nightingales sing.

They hadn’t been there but an hour or two

Till out of his knapsack a fiddle he drew

The tune that he played caused the vallies to ring.

O harken, says the lady, how the nightingales sing.

Pretty lady, pretty lady, ’tis time to give o’re.

O no, pretty soldier, please play one tune more.

I’d rather hear your fiddle at the touch of one string

Than to see the waters gliding, hear the nightingales sing.

Pretty soldier, pretty soldier, will you marry me?

O no, pretty lady that never can be.

I’ve a wife back in London and children twice three.

Two wives in the army is too many for me.

[1] As I was a walking one morning in May

[2] Indicative of a 19th century variant… songs reflecting soldiers going off to serve in India generally start showing up in the mid-19th century although soldiers from England had been, to a lesser degree, been serving to protect the interests of the Crown and of the East India Company since 1612.